Book Review (12/25): The Second Emancipation

Explorations in African leadership

The Second Emancipation: Nkrumah, Pan-Africanism, and Global Blackness at High Tide, by Howard W. French

Thank you for being a regular reader of An Africanist Perspective. If you haven’t done so yet, please hit subscribe to receive timely updates on new posts along with over 31,000 other subscribers. All new regular content is free. Book reviews and the archives are gated.

In The Second Emancipation, Howard French delivers a masterful exploration of the global political history of Africa in the first two thirds of the 20th century. French’s vessel is the biography of Kwame Nkrumah, which he uses to guide readers through a captivating and readily accessible journey through the rapidly changing world in which the former Ghanaian president lived.

I strongly recommend the book for the deeply-researched (intellectual) history of Pan-Africanism, Black Internationalism, the global decolonization movement, and the well-rounded interrogation of Nkrumah the man and politician. It’s easily my favorite book of the year.

This review will focus on what we can learn about leadership and development policymaking from Nkrumah’s tenure atop Ghanaian politics.

I: The wages of postcolonial decline and collapse of the quality of African leadership

A striking feature of contemporary Africa is the almost total lack of historically-aware and self-consciously strategic leaders. To be blunt, most African countries are led by two-bit rent-seekers with astonishingly low ambitions. The same leaders are fairly comfortable being at the bottom of the totem pole of global elites. You see this in how they unthinkingly batter away their countries’ natural resources, human capital, and market access for the proverbial trinkets. Too often you get the sense that they are simply not interested in addressing their societies’ problems.

In this post — and with reference to the life of Kwame Nkrumah — I argue that leadership matters, and that things weren’t always this bad on the Continent. There was a time when many (admittedly imperfect) African leaders were intrinsically motivated to be ambitious and willing to deploy whatever little leverage they had to expand their own agency, policy autonomy, and strategic independence — all with a view of improving their citizens’ living standards and their nations’ standing in the world.

My aim herein is twofold. First, it’s to shed some light on how we ought to define “good leadership” on Continent. Second, it’s to define how Africa’s leaders can help the region avoid a calamitous future as far as human welfare goes.

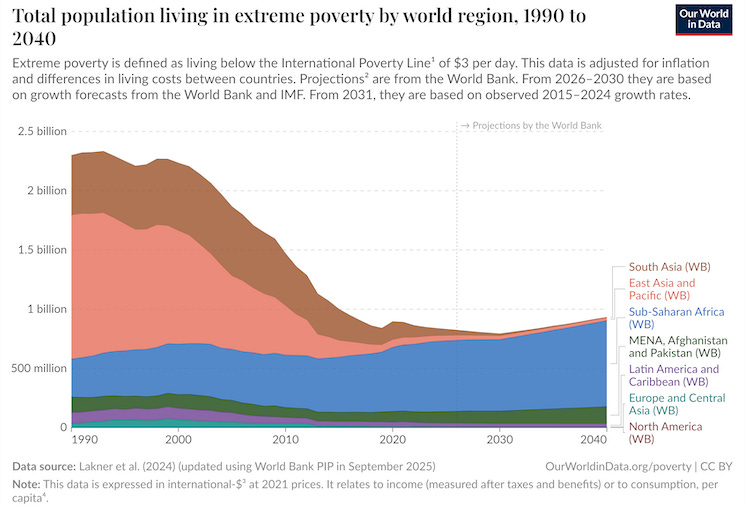

There’s no way to sugarcoat the current state of affairs on the Continent and what it means for the future. Africa is rapidly becoming the last world region to be ravaged by extreme poverty and its manifestations. Importantly, most African states remain weak and unable to secure their citizens, provide essential public goods and services, or create enabling conditions for commerce at scale. It’s my contention that coordinating out of this mess will require a much higher caliber of leaders than the Continent currently has.

For emphasis, the facts and figures quantifying decades-long policy failures across the Continent are grim. 600m people in the region lack access to power — this is over 80% of the global population without power (Africa represents 18% of global population). Only 20% of Africans use clean fuels to cook (those without access represent 43% of global total). Of the 58m primary school age children worldwide who aren’t enrolled, 33.8m are in Africa. An astonishing 60% of African 17 year olds are not in school. Furthermore, the region significantly lags the rest of the world on research — a reflection of the sorry state of higher education in the region. The atrocious levels of under-investment in education extend well beyond education. 31.7% of kids in the region are stunted (only South Asia records similar levels). Under 40% of Africans have access to piped water in their homes. The region’s economies remain largely informal, and create a mere 30% of the needed annual formal jobs. Over 80% of jobs are in the informal sector. It is no wonder that the last few years have seen young Africans protest their governments at risk of life and limb. A majority now openly support coups. The list goes on and on.

Sure, there has been some recent progress on key development indicators. Infant mortality rates are relatively lower (although still unconscionably high). Life expectancy is up. Despite enduring challenges to quality and access, education attainment levels are inching ever higher. And many countries continue to post economic growth rates that outpace their population expansion.