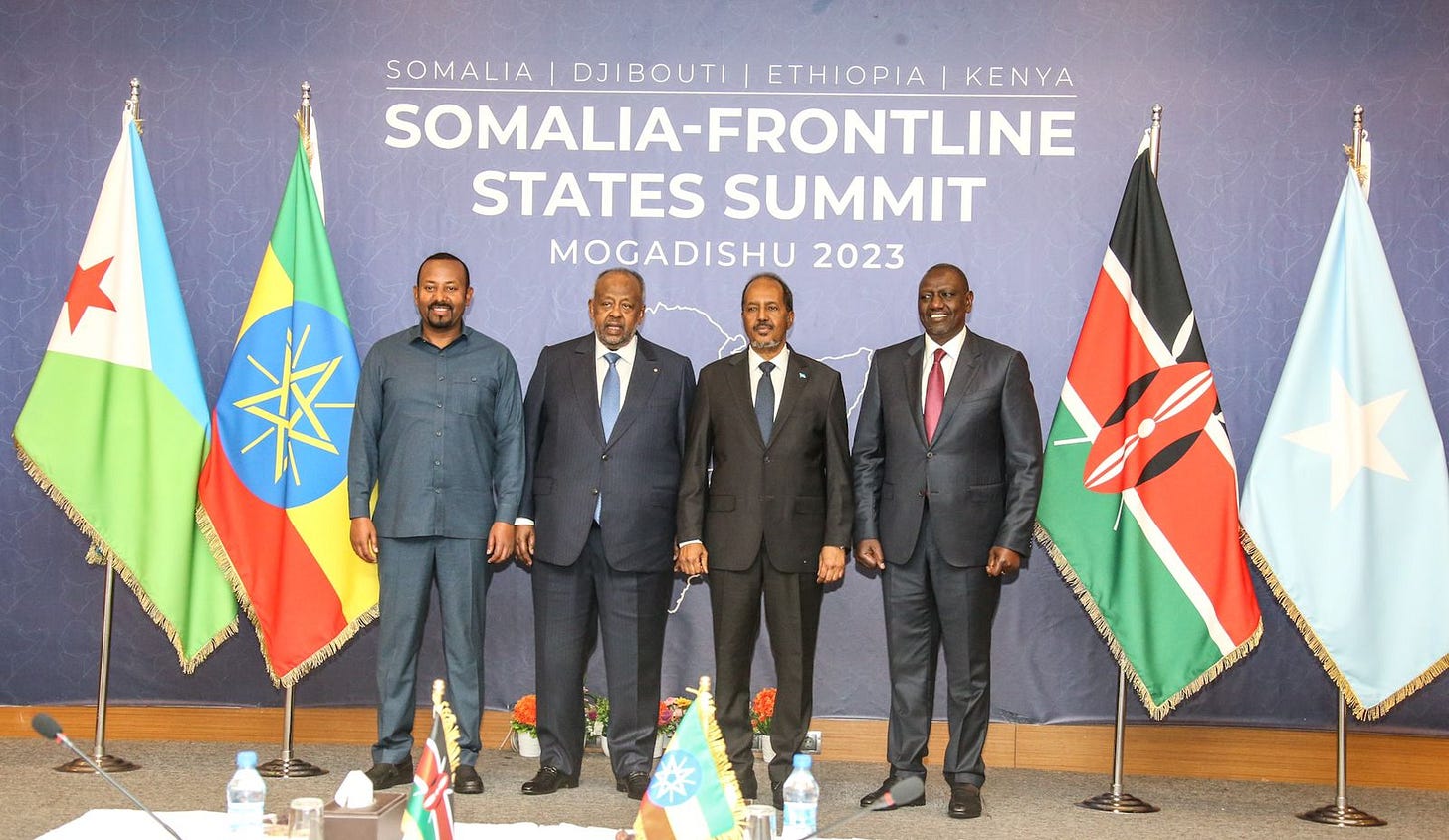

Book fairs in Mogadishu are a thing. The city is experiencing a property boom. Al-Shabaab appears to be on the back foot, with several clans abandoning them in their strongholds. The African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) is scheduled to depart in 2024. Last month the East African Community (EAC) started assessing Somalia’s readiness to join the economic bloc. And just last week presidents from Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Kenya were in Mogadishu to talk peace and regional cooperation.

Is this the beginning of the end of Somalia’s decades-long civil war?

I have a number of reasons to be cautiously optimistic. First, after more than a decade of “managed democracy,” Somali elites appear to have internalized the need for peaceful politics. Consequently, the institutionalization of politics in the country is underway. Second, Somalia’s fractious clan politics no longer work in favor of Al-Shabaab. A crippling drought may have pushed populations under Al…