The international development community isn’t adapting fast enough to official aid cuts. That’s a big problem.

On the urgent need for a pivot to spending more time trying to supporting specific countries interested in boosting their state capacity; and catalyzing commercial revolutions in low-income countries.

Thank you for being a regular reader of An Africanist Perspective. If you haven’t done so yet, please hit subscribe to receive timely updates on new posts along with over 33,000 other subscribers. New regular content is free. Book reviews and the archives are gated.

I: Wallowing in nostalgia is not a strategy

Early last year I urged us all to quickly move past the old foreign aid paradigm (see here, here, here, here, and here). In doing so I wasn’t denying the important positive impacts of foreign aid, especially in the health sector. Instead, I wanted us to imagine a world where the delivery of aid didn’t engender aid dependency (regardless of the impacts) or distorted recipient countries’ political economies and stunted their political and economic development. I firmly believe that if done well — i.e., if aligned with recipients’ objective development priorities — development cooperation, of which aid is a component, can bolster low-income countries’ journey towards structural economic change.

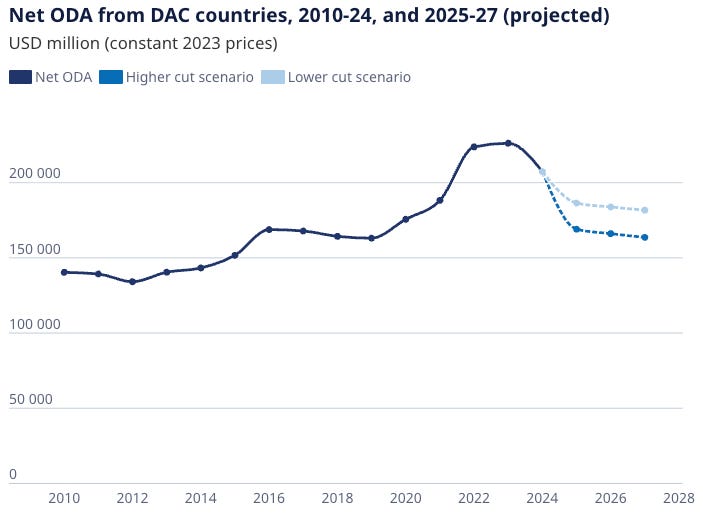

Since then things have moved fast. In 2025 total official development assistance (ODA) was projected to decline by 10%-18%, coming on the heels of a 9% drop in 2024. In addition, many donor countries have also continued the trend of reclassifying domestic spending on immigrants as “foreign aid.”

Importantly, the U.S. government, which disburses lots of aid cash and therefore is an agenda setter, is in the process of radically reforming how it provides foreign assistance to developing countries. According to the New York Times:

Over the past month the U.S. has signed agreements with 16 African countries to provide more than $11 billion in health aid over the next five years, and is negotiating dozens more deals with governments in Asia and Latin America as well as Africa.

The new commitments represent a steep drop in the health aid that the United States contributed before President Trump ordered a review of foreign assistance on his first day in office last year. According to an analysis by the nonprofit Partners in Health, health funding under the agreements would drop by 69 percent to Rwanda, 61 percent to Madagascar, 42 percent to Liberia and 34 percent to Eswatini, where a quarter of adults live with H.I.V.

Nevertheless, the deals are being welcomed by governments and some analysts in Africa as a significant shift that could increase country autonomy and make health systems stronger and less reliant on international largess. Others, however, say the agreements were negotiated with countries that had no leverage and demand conditions that are unattainable, especially in places where people are most in need of help.

The last paragraph above is particularly important, for two reasons. First, it’s easy to evaluate America’s aid policy pivot on the basis of the character of key decision-makers in Washington; or with reference to the old aid paradigm. Both would be a mistake. It’s certainly fair to critique specific policy choices, especially when they cause what seem like gratuitous harms in the real world. However, the fiscal realities in donor countries are what they are. Budgets are tight and will get tighter — considering emerging pressures for military build ups. The cuts are here to stay, and could quickly get worse. In addition, the new global geopolitical environment will put pressure on countries to use aid more nakedly for geo-strategic purposes. We should all get used to the idea of ever more direct political control of aid allocations. And the process of getting used to this reality should start with getting over the specifics of U.S. politics. Other non-U.S. donor countries are cutting aid, too. Opinions regarding the domestic politics of donor countries should not become a blinker against consideration of alternative pathways away from aid dependency. In the same vein, unnecessary catastrophizing about the plight of low-income countries must be avoided at all cost.

That said, I acknowledge that there will be clutching at straws. Many will observe, for example, that America is not really retreating, since the U.S. Congress is still appropriating funds towards America’s international obligations (including to multilaterals). That perhaps everyone can just wait out specific administrations or public opinion cycles. Yet the overarching point is the irreversible erosion of confidence in the predictability of flows. Only irresponsible governments (or organizations) will fail to notice that future flows will be highly volatile, at best.

Second, it matters a great deal what governments and elites in aid-recipient countries think of these changes. One of the greatest tragedies of the last 50 years has been the relative unimportance of local elite agenda setting in developmentalist projects in low-income states. Some of this was due to the types of leaders in these countries, and the weakness of the states they run. But another driver was the deliberate sidelining of local institutions and elites (sometimes with good reason, but often because of unjustifiable prejudices). The great Thandika Mkandawire succinctly historicized this problem:

With the crisis of the 1980s local elites became the subject of derision as the state structures they dominated failed miserably. Many adherents of the modernisation theories began to lose faith in local elites on whom the entire project of modernisation rested. For some the African leaders were impostors dressed up in Western garb but tragically primitive. The failure of the African elite to rally around a common project and their failure to resolve many collective problems they confronted undermined their legitimacy in the eyes of their own people. Not surprisingly within Africa itself this led to debates on governance and accountability long before this became a donor concern. The ascendant rational choice characterised local elites as ‘rent seekers’ and dismissed their developmental efforts and institutions as ruses for extracting rents from society.

The contempt for the local elite did not spare the academic community. The condescending running comments by visiting scholars on African scholarship and the self-serving devaluation of local expertise by visiting consultants became quite common. NGOs also joined the university bashing. They argued that focussing on higher education was privileging certain forms of knowledge while ignoring other sites for the production of knowledge. Instead they advocated ‘community based’ or more ‘participating’ processes in which ‘grassroots’ were the agents of their own emancipation. NGOs were said to possess considerable knowledge about strategies for by-passing, weakening, co-opting or coping with elites and the responses of those elites to such strategies.’

It is high time everyone abandoned the prevalent blanket disdain for local elites and institutions in aid-recipient countries. Admittedly, most of these institutions and the individuals that run them are imperfect. However, they are certainly not irrelevant. It follows that ignoring them or devising schemes to work around them is a recipe for failure. To be blunt, local political economy realities must be part of our understanding of the new aid dispensation.

For example, it would be foolish to ignore the fact that there is a receptive audience in these countries to the idea of more aid flowing in the form of government-to-government budget support, as opposed to a model dominated by implementing NGOs. With this in mind, there is no reason not to have a good faith consideration of the emerging U.S. model of aid matching (see below). Implementation will vary, and not all countries have the minimum levels of fiscal capacity or space needed to make it work. But it nonetheless raises interesting questions regarding the possibility of strengthening low-income states’ bureaucratic-administrative systems that collect revenue and deliver essential services (emphasis mine):

The administration’s new mode of providing health aid differs significantly from the previous funding model. Now U.S. support is being conditioned on a cofinancing commitment from the partner country — Washington will give Nigeria about $2 billion over five years, for example, if the Nigerian government increases its current health budget by $3 billion in that period. In many cases, the new commitments that governments are making represent a large hike in their health spending — and it’s not clear, in countries with faltering economies and huge debt burdens, where those funds will come from.

More broadly, what these changes ask of us is a willingness to reimagine aid delivery mechanisms — whether it is official or through private charities. As Mkandawire warned us, pointing to past state failures is not a reasonable veto against this possibility. This is for the simple reason that state weakness on the Continent is endogenous to modalities of aid delivery. Those who substituted for the state in the NGO-ization wave of the last 35 years partially contributed to the weakening of the African state. Furthermore, both the extent of such weakness and/or the impossibility of positive improvement tend to be grossly exaggerated out of ignorance or self-serving motivations. We shouldn’t let what Mkandawire calls the “pre-analytic predisposition of the observer” cloud the debate.

II: Imagining the way forward: What is the best way to catalyze transformational economic development?

To be able to constructively imagine the way forward, it would be helpful to be on the same page regarding the goals of aid. Here, two pieces come to mind. First, last year Zainab Usman expertly argued in Foreign Affairs for disentangling foreign aid from development assistance:

Proponents of global development now face a choice. They can wait for attitudes in donor countries to shift back toward support for foreign aid at some point in the distant future. Or they can reimagine the entire concept of global development, detaching it from aid and rooting it instead in industrial transformation: helping countries shift from subsistence farming, informal employment, and primary commodity production toward manufacturing and services. In truth, the aid industry was already adrift. Its interventions had become spread too thin and often failed to address the key obstacles that poorer countries faced as they tried to upskill their workers, build energy and transport infrastructure, and access new markets.

This is the best place to start. It would seem eminently reasonable to have conceptual, organizational, and operational separation between emergency humanitarian assistance during crises like war and famine, and support for transformative economic change and development. Yet the global aid industry operates with significant overlap between the two. The notion of permanent crises even in non-emergency situations — which permeates most project designs, organizational structures, and delivery approaches — both inhibits successful assistance towards structural economic change and entrenches dependency.

Second, Sarah Bermeo wrote a short description of the purposes of foreign aid from the perspective of the U.S. government (and which applies to other donors as well). These include, fulfilling popular mandates in support of solidarity with foreigners; providing global public goods (like stopping the spread of infectious diseases); creating markets and strategic economic allies; investing in soft power; and increasing coercive leverage over others. This is an important piece to inoculate all who naively get carried away with the supposed benevolence of aid. It is important to remember that politics, differential power relations, and attention to self interest always lurk in the background; and that these factors all have implications for how we should think about maximizing the developmental impacts of foreign aid.

At this juncture, I should note that I will disappoint readers looking for off-the-shelf solutions that can quickly be packaged in a fundraising deck.

Like all good policy change processes, the most important things to get right regarding the future of the aid industry would be to 1) understand the nature of the problem that we are trying to fix; and 2) have a clear sense of what success looks like. Beyond that, everyone should be open to iteratively learning by doing depending on temporal and spatial contexts. This approach may not satisfy those who only think in terms of time-bound narrow projects, but it is the way to go.

So what are we trying to fix and what would success look like?

The problem we are trying to solve for is how to deliver development aid and humanitarian assistance in a manner that helps countries along in their journeys towards structure economic change; and which does not entrench aid dependency. Of course aid alone can never cause countries to experience structural economic change. The point here is that it can help, or at the very least not hinder that process.

In terms of success, we should keep the metrics simple and clear. We will know we are on the right track if, all else equal and with attention to the points raised by Usman and Bermeo, reforms in the aid sector reorient delivery mechanisms to achieve two objectives: 1) facilitate the strengthening of state capabilities in the provision of essential public goods and services; and 2) help catalyze private sector growth and mass job creation within large firms. These objectives also apply to humanitarian assistance. For example, there is no reason why the delivery of food aid in northern Kenya (or in Somalia or South Sudan) should not at the same time be viewed as an opportunity to meaningfully strengthen food security in Eastern Africa (including via more efficient agricultural supply chains and markets). The point here is that the habit of treating the aid sector as an enclave economy that operates outside of basic laws of economics, policymaking, and local political economy realities must stop.

III: A much-needed conceptual leap

Reorienting the aid industry to reduce dependency and contribute towards structural economic change in aid-recipient countries will require a conceptual leap. The starting point should be to understand the role of aid in the process of national development. Here, it is worth recalling a question from the excellent Yuen Yuen Ang:

Is there any economy that escaped poverty (ie eliminated poverty at scale) through foreign aid or by giving handouts like chicken and cash?

The simple answer to this question is a resounding no. The long answer requires a few paragraphs.

But first, some clarifications. To be clear, I read Ang not as an argument against foreign aid, humanitarian assistance, or direct assistance to low-income households. It is an argument against operationalizing foreign aid as an end in itself; or aid as perennial emergency interventions devoid of any consideration for the bigger picture. With that in mind, it’s worth interrogating how we got to a world of aid as handouts (and workshops), as opposed to aid as a helping hand in the journey towards national development.

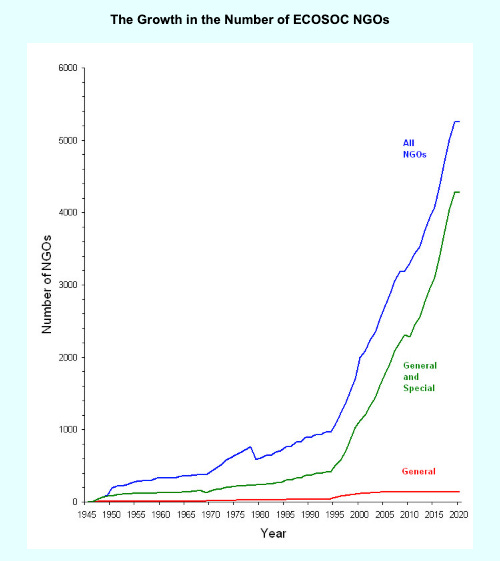

I see two important drivers. First, there was the problem of failed state-led developmentalism in the 1970s and 1980s — which accelerated the NGO-ization of development assistance after the 1990s as a way of coping with state retrenchment (again, Mkandawire was spot on in arguing that this perceived weakness was both ahistorical and overstated). The intensification of NGO-ization was evident, for example, in the explosion of the number of NGOs in consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council (see graph, the number currently stands at over 6,000). For reference using a specific country example, in 2022 Kenya reported 12,000 registered NGOs, up from just over 400 in 1991.

The effects of NGO-ization were exacerbated by new donor conditionalities and forms of global activism that crowded in all manner of pet goals into aid programs. Thus was born the very expensive “Christmas tree” approach to program design, whereby attention to internal organizational politics, trendy fads, and public virtue signaling overrode actual delivery. The first victim of aid being spread thin to serve too many goals was efficiency. Donors’ deliberate complication of programs (by crowding in everyone’s pet initiative) then became a defensible justification to bypass weak state delivery mechanisms.

Second, the knowledge management regime that emerged in the 1990s and early 2000s markedly shifted incentives. Once aid became about helping poor people without having to deal with their corrupt governments and otherwise bad elites, the moral angst over harm and efficacy on the part of donors and aid workers rose several notches. You then got two types of aid workers — those who believed that merely helping the global poor justified being in the business (and anyone who got in the way just didn’t get it); and those who were obsessed with measuring and therefore achieving high efficacy (and eliminating harm) as a way of fulfilling the moral obligation to the poor. Both types of aid workers and their attendant approaches produced timidity and self-righteous solipsism on the part of donors as a collective.

Obsessive control and barely-disguised paternalism became the norm, which further aggravated the problem of excessive NGO-ization and declining state capacity. Aid got ever indistinguishable from domestic charity work — for a dollar a day you can save the life of a child in Bangladesh or Nigeria! And we have the data to back up that claim!

Meanwhile, the academic research on development (especially among development economists) got significantly better; while the arguably more important policy research about how to do development in specific places stagnated or declined.

Here it is worth invoking Lant Pritchett’s concise distinction between charity work and development work:

The development question is: “How can the people living in Niger come to have broad based prosperity and high levels of wellbeing?” The charity question is: “If some agency (perhaps of a government) is going to devote a modest amount of resources to targeted programs that attempt to mitigate the worst consequences of a country’s low level of development, what is the most cost-effective design of such programs?”

Now, reasonable people can debate whether this distinction matters. Some may argue that should be free to spend their money as they wish. The problem, though, is that aid money tends to have significant distortionary effects on policymaking in low-income countries. Plus donors aren’t just plucky lone rangers. More often than not they amplify their mistakes through the actions of powerful multilateral organizations and in the shaping of policymakers’ worldviews. For these reasons, it would be optimal if aid was as aligned as possible with aid-recipients’ national development priorities, and not administered like it was domestic charity work.

Which brings us back to Yuen Yuen Ang. As a matter of course, the process of reinforcing state capabilities towards national development and aiding private sector led commercial revolutions will require a significant conceptual leap. Importantly, that leap must be characterized by a willingness to let aid recipients and their policymakers be the masters of their own destiny. This is because the process of economic development is dynamically complex. It is also typically imbalanced. What this means is that the road to economic takeoff is neither linear nor as simple as following a recipe expressed in tight project timelines. It doesn’t matter how much we complicate or intellectualize that presumed recipe. Ang makes this point very clearly:

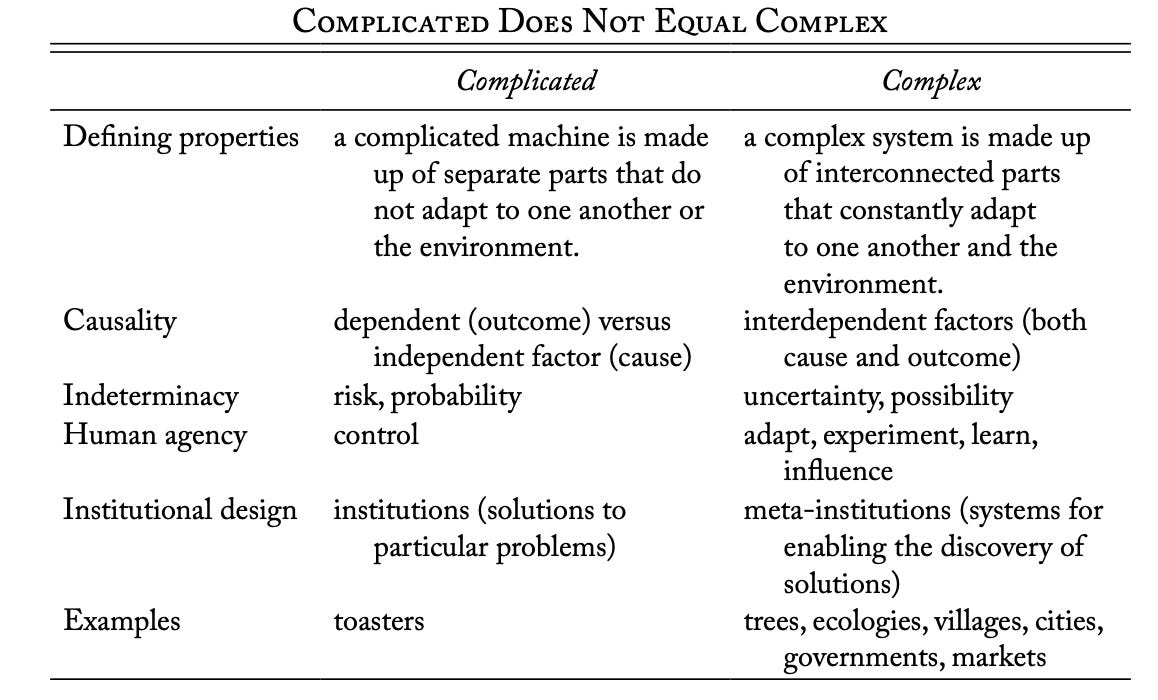

Complex does not mean complicated, just as trees are not toasters. Complicated things are made of many separate parts that do not adapt to one another or the surrounding environment—machines are good examples. A toaster is a machine that is exactly the sum of its parts. To assemble a toaster, follow the instruction manual and put the parts in order (unlike Michelangelo’s famous depiction in The Creation of Adam, a final magic touch is not needed to bring it to life). When dealing with machines, processes are linear and outcomes can be controlled. Press a button and a toaster will produce a predictable action: crisp, warm bread pops up.

Complex is the opposite of complicated. Whereas machines are complicated, systems are complex. A system is made up of interconnected elements that adapt to one another and the environment, for example, a tree. The term adapt is not just a fancy word for change. Rather, it is a particular type of change, expressed by John Holland as the process by which an agent “fits itself to its environment.”19 This process has at least three key mechanisms: variation (generating alternatives); selection (choosing among or assembling alternatives to form new combinations); and retention (keeping and diffusing a given solution or exploring new ones). Many adaptive iterations result in evolution—that is, substantial changes in a given system.

… We face risk in complicated worlds but uncertainty in complex ones. Mechanical situations pose risks—that is, the probability that certain anticipated outcomes may occur (when a toaster breaks down, a user finds it annoying but not surprising). By contrast, complex systems are constantly adapting and thus generate uncertainty—that is, possibilities beyond anticipation and planning. Some possibilities are terrible, such as financial crises and pandemics. Yet some possibilities, such as groundbreaking innovations or stumbling into one’s passion, are marvelous. To extinguish uncertainty is to extinguish possibilities, both terrible and marvelous.

Admittedly, those who view themselves as the moral arbiters of the plight of the needy in the developing world, and/or those who cannot give without the warm glow of quantified impact would find it mighty hard to operate in Ang’s complex world. Which is to say that embracing complexity in development will necessarily require trusting aid recipients to chart their respective paths to national development. Notice that the points raised by Usman and Bermeo can readily be layered on top of our world where aid recipients are the agender setters with reference to their dynamically complex contexts.

In concrete terms, embracing complexity will require four key conceptual adjustments:

A philosophical and temperamental discarding of models of aid delivery that cultivate paternalism and dependency: Aid alone cannot cause national development. But it can help countries along in that journey. It follows that aid recipients must always be on the driver’s seat as far as research, policymaking, and implementation go. This is a mind shift that’s also needed in low-income countries. Aid, including geopolitically-motivated assistance, has the highest efficacy when it serves specific national goals.

A fundamental shift in popular understanding of how structural economic change happens: I often joke that the field of international development should be the exclusive preserve of economic historians. This is because they often bring to the table a healthy temporal understanding of the complex process of economic development. There are no recipes that can be scaled globally. Ideas and localized production of “useful” knowledge matters. You cannot wish away interest group politics. And societies learn by doing.

Embrace of the political economy of policymaking in developing countries: All countries have domestic politics. And policy that is designed to circumvent politics ultimately fails on first contact with this reality — precisely because economic change is inherently redistributive (in terms of both economic and political power), and therefore highly political. Furthermore, “good policies” without strong political constituencies to sustain them tend to be a waste of time. You need developmentalist coalitions to make sure that reforms needed for structural economic change stick.

Agree that ignorance is not a viable strategy: To reiterate, academic research and policy research are two completely different things. With this in mind, knowledge production and management should focus on policymaking and implementation in specific contexts. A direct implication of this shift is that we should see more investments in localized knowledge production. Let a thousand think tanks bloom in developing countries. Deliberately choosing ignorance about specific contexts, and then hiding behind scalability of individual studies across contexts is a doomed strategy. This is not to say that countries cannot learn from each other. Far from it. The point is that policy research necessarily has to mirror the iterative nature of policymaking and implementation. And you only get to do that properly when studying a specific policy being implemented in a specific institutional/political context.