There will be no economic takeoff in Africa without lots of large (private sector) firms

On why African states’ jobs agenda must focus on catalyzing firm growth (and not disorganized investments in micro-entrepreneurship)

Thank you for being a regular reader of An Africanist Perspective. If you haven’t done so yet, please hit subscribe to receive timely updates along with over 29,000 other subscribers.

I: African economies desperately need lots and lots of formal sector jobs

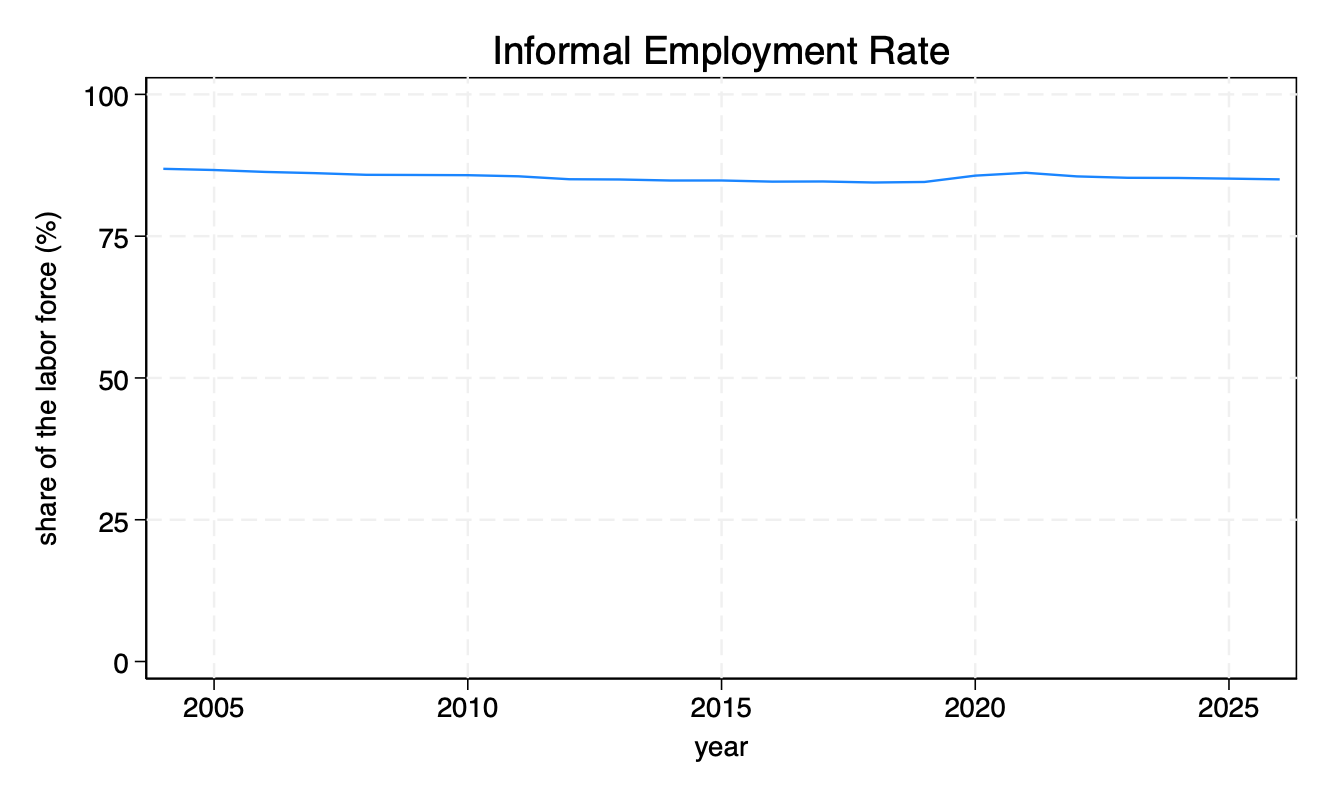

The rate of informal employment in Africa is high, and basically hasn’t budged over the last 20 years. The dearth of formal sector jobs presents an existential crisis for African countries. Over 10m young Africans enter the labor force each year, but the region only creates 3m formal sector jobs. Most workers get absorbed into the informal non-agricultural sector. Fewer every year settle for farming, while many try to migrate outside of the Continent in search of jobs.

One of the drivers of the recent rise in protests is young African’s deep frustration with being jobless or underemployed and trapped in stagnant economies m…