How African policymakers should prepare for the coming commodity boom

Projections point to elevated commodity prices over the next decade. Here's how African policymakers can avoid mistakes of the past.

Thank you for being a regular reader of An Africanist Perspective. If you haven’t done so yet, please hit subscribe to receive timely updates on new posts along with over 33,000 other subscribers. New regular content is free. Book reviews and the archives are gated.

I: Important lessons from the last commodity boom (2000-2014)

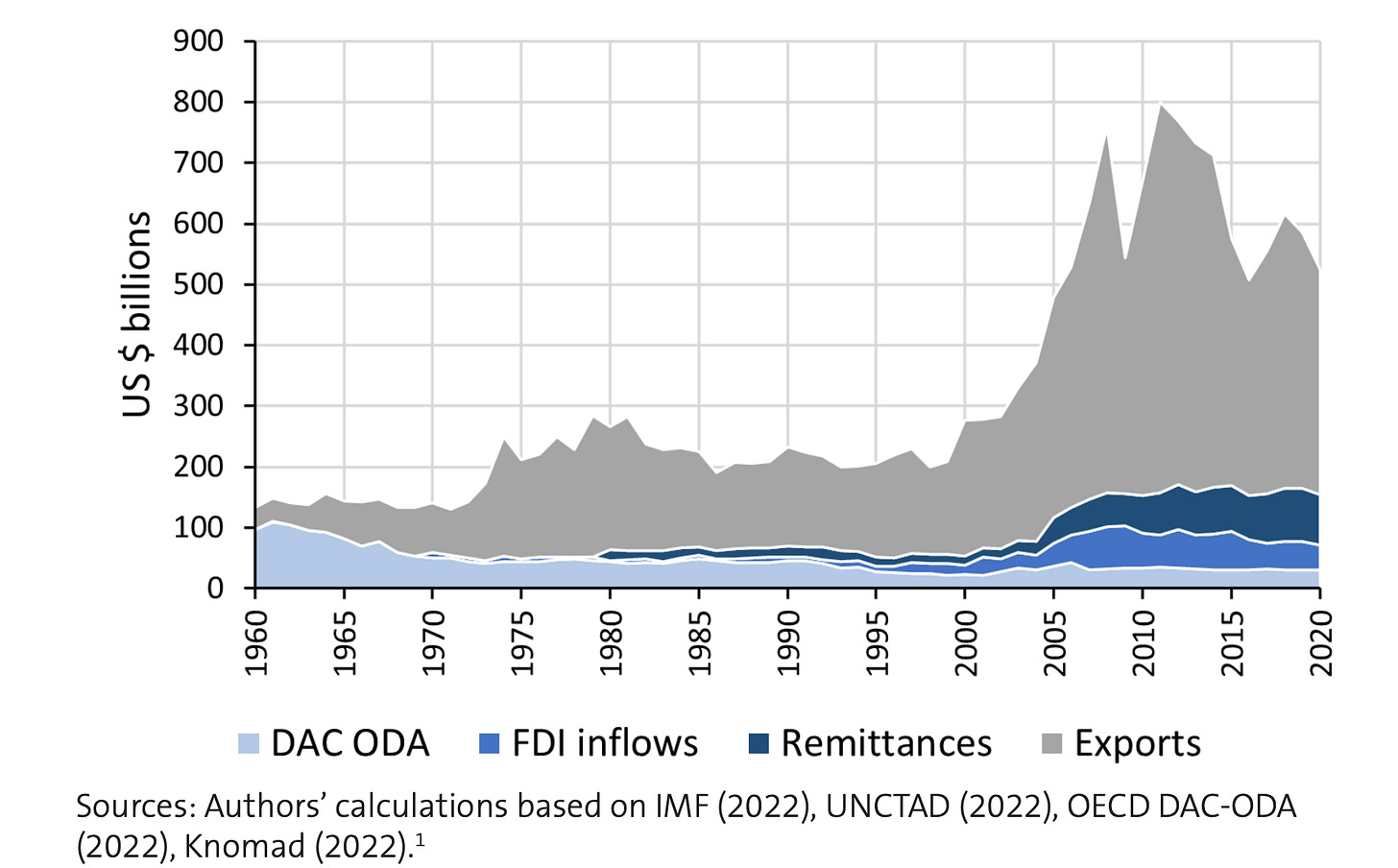

An important driver of African countries’ improved economic performance and surging exports in the early 2000s was the China-fueled commodity supercycle. Between 2000-2014 regional exports nearly quadrupled, per capita income rose by 37.1%, while the share of people living in extreme poverty declined from 62.5% to 45.7%. Overall, the first decade and a half of this century saw the steepest improvements in human welfare on the Continent since the rapid post-independence economic expansions (circa 1960-1976).

Then the music stopped. China’s economic slowdown after 2014 resulted in slower growth rates in many African countries. Thereafter incomes plateaued or declined, and poverty reduction virtually stalled. Meanwhile, commodity-fueled government borrowing (including in private credit markets) during the boom years and the high cost of debt servicing (which many argue came with a steep “Africa penalty”) shrunk fiscal space in many countries.

Importantly, the return to the private credit market did not discipline public finance management in the region. While corruption consumed a non-trivial share of borrowed cash (see the tuna bond scandal), the more pressing challenge was inefficient and/or wasteful public spending. To this end, a number of governments even borrowed against yet-to-be-proven resource reserves. It did not help that many of the high-ticket capital expenditures failed to yield projected growth (in many cases money was simply misspent), or create the jobs that the Continent desperately needed. Tax collection stalled, even as economies experienced nominal expansions. COVID plus similarly inflationary global geopolitical upheavals exacerbated these problems. Many countries faced fiscal distress. A few defaulted. The aftershocks of these challenges will undoubtedly have long lags into the future.

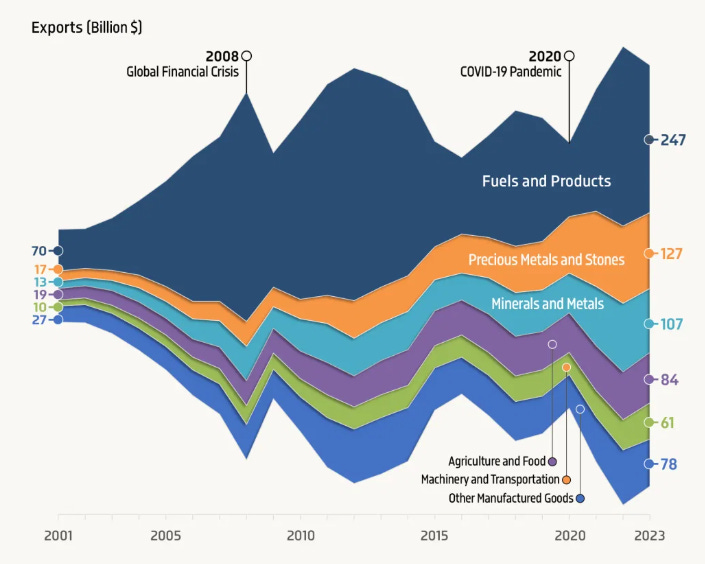

What exactly did African countries export during the commodity supercycle? The disaggregated data highlight the dominance of fuel exports over the 2000-2014 period (see above). However, it is also clear that agriculture, ores and metals, and manufactures also saw permanent increases. Notably, commodity exports during this period did not involve any significant value addition (despite all the conferences, workshops, and talk of “local content”). As a result, the overall impact on formal employment and incomes was largely muted.

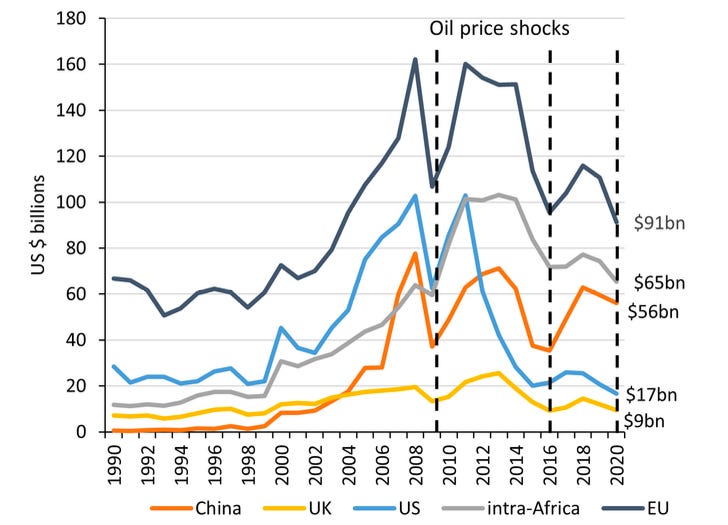

Another change that happened during this time period was the rise in prominence of both intra-Africa trade and the Africa-China trade (see above). The rise in Chinese demand is under stable, but what explains the rise of “Africa” as the Continent’s second most important trading partner? More research is needed here to unlock the specific mechanisms at play, but it would seem that exposure to global markets (both as exporters and importers) substantially unlocked intra-Africa trade.

My hunch would be that improvements in transportation and logistics and export orientation (in terms of business outlook but also laws and regulations) — with an eye on new markets in China and Europe — had positive spillover effects with regard to regional trade. All those new roads, airports, and ports must have made a difference. The increase in intra-Africa trade was especially noticeable within the RECs. This was above and beyond what would be predicted by standard models of commodity booms which assume that a wealth effect from high commodity prices would mechanically increase demand (including from other African countries).

To understand how general openness to global trade can transform economies it is worth looking at the FDI data. The EU’s FDI into Africa during the commodity boom targeted mining, manufacturing, and financial services. Over the same period, Chinese FDI targeted energy, transport, metals, real estate, utilities, finance, and agriculture. In other words, trade openness (especially vis-a-vis China) led to denser commercial relations than what would’ve been predicted by the narrow commodities that may have been the original basis for growing economic ties.

II: Will this time be different?

Now, again, we seem to be entering a new commodity supercycle that will likely last through 2035 (projections vary quite a bit). This time, however the outlook is mixed across different commodity sectors. In addition, I think that African economies will do marginally better than the last time.

First, fuel exports will not dominate. Oil and gas prices are projected to experience downward pressure into the medium term. This should signal to African policymakers to ensure that they lock in, as much as possible, domestic and regional consumption into their hydrocarbon plays (even if it is just over a transition period).

Second, agricultural commodities are likely to face higher volatility relative to the last time (albeit always at a higher price level than last time). Again here, the best insurance against global cyclical pressures will be improving agricultural productivity with a focus on food crops with robust domestic/regional demand; and as much value addition as possible on the so-called cash crops before export (Ghana’s ambition with cocoa processing is therefore very welcome). Governments should also seriously support African private firms to venture into the commodity trading business. One could argue that investments towards a Green Revolution were hobbled by weak state capacity in the 1960s/1970s, and then structural adjustment of politics and policymaking in the 2000s. But what will the excuse be this time? State capacity, the technical know-how, and the logistical links in pivotal countries that can provide strong demonstration effects are good enough. Plus there’s (finally!) a massive regional (and global) market. Which is to say that there’s no excuse this time.

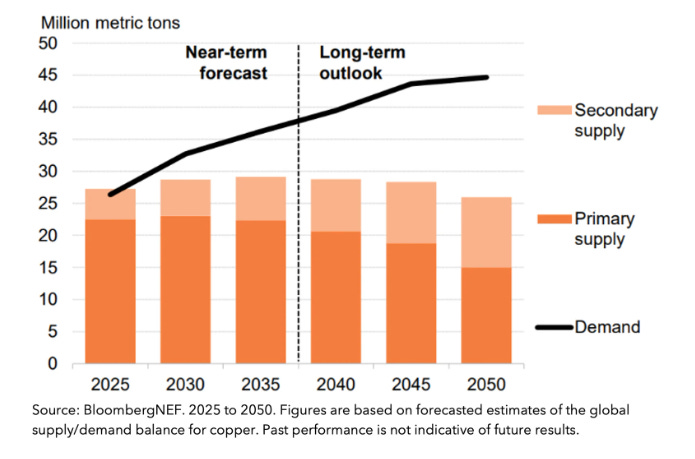

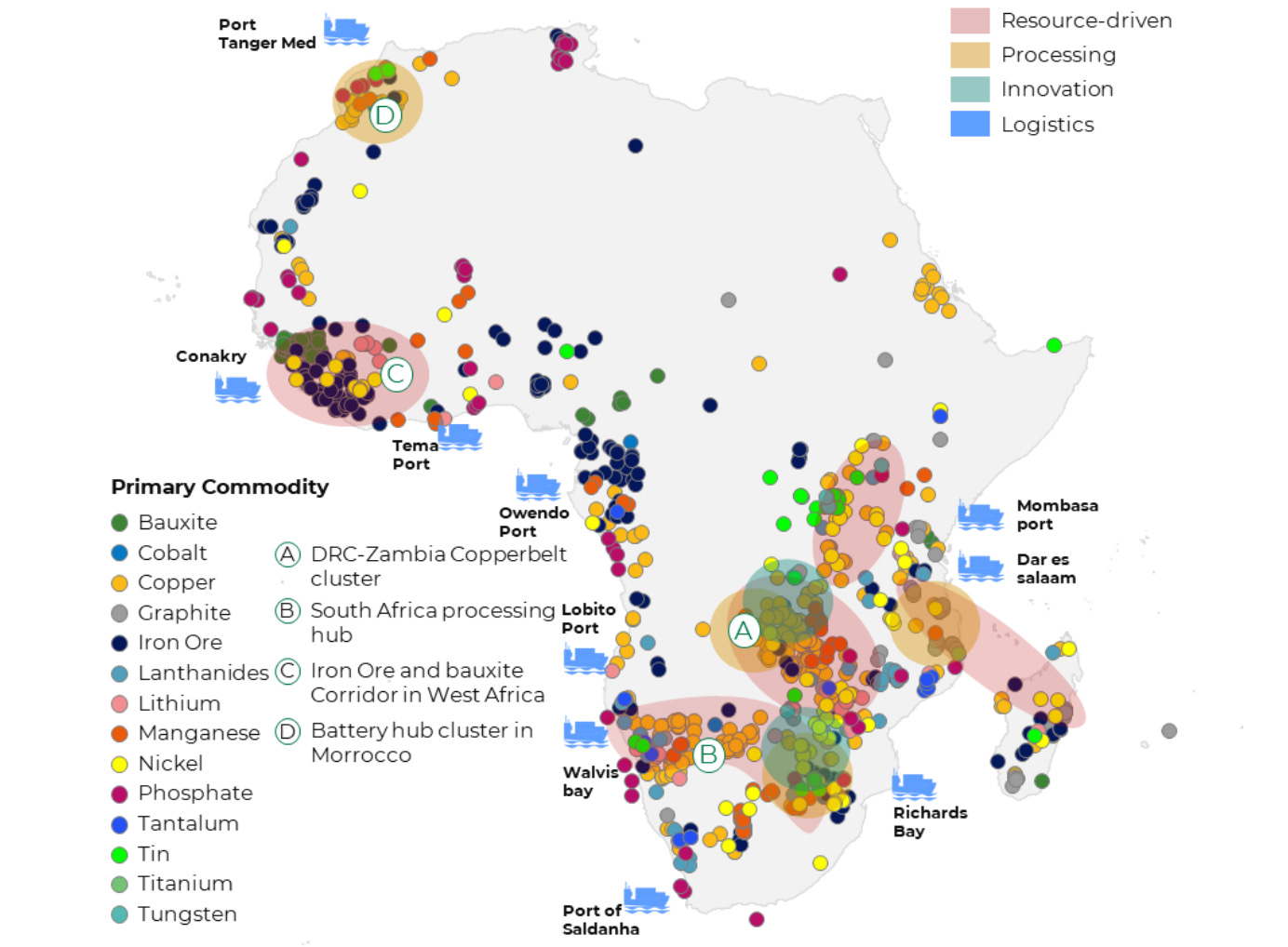

Third, precious and industrial metals will lead the boom. Demand for precious metals, especially gold, will be driven by the search for safe assets in the wake of heightened global economic uncertainty and geopolitical risk. The value of regional gold exports is already up by more than 50% over the last five years. Demand for industrial metals will be fueled by the AI-driven expansion of data centers and investments in energy transition. Coming on the back of almost a decade of underinvestment in mining, meeting the rising demand for both industrial and precious metals will require significant FDI in the medium term.

There are already a number of concrete examples of these developments — especially within SADC and the EAC, which will power much of the coming supercycle on the Continent. Zambia plans to more than triple annual copper production (to 3m tonnes) by 2031. Its northern neighbor, the DRC is already at it. Once fully operational the DRC’s Kamoa-Kakula complex (run by Ivanhoe Mines — see below) will be the third largest copper/cobalt mining operation in the world. The DRC’s current total production stands at 3.2m tonnes, and will likely peak at 3.5 tonnes a year after 2029 (unless there are new discoveries). South Africa and other Southern African countries have also recently embarked on investing in prospecting and domestic refining of industrial metals before export.

In West Africa, Guinea’s exceptionally-rich $20b Simandou iron ore operation is finally becoming a reality, complete with a new rain link. Guinea also plans to expand the refining of bauxite from zero to 7m tonnes by 2030 (it is the world’s largest exporter), alongside other major investments in solid mineral exploration. Ghana is ramping up gold production, and intends to increase its bauxite production from the current circa 1.8m tonnes to 6m tonnes (in addition to expanding local processing). Besides Guinea and Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire and Nigeria are the other West African countries likely to appreciably increase production of industrial metals. Finally, Cameroon and Gabon will be the two countries to watch in Central Africa.

Fourth, there is the geopolitics of the coming commodity supercycle. The U.S. recently launched Project Vault, a $1.2b move to stockpile critical minerals. China already raced ahead with stockpiles and processing capacity. Overall, there is a global race to secure access to industrial metals and “critical” minerals.

There are already murmurs about how African policymaking are approaching this moment. For example, at this year’s Mining Indaba, a South African Minister accused his Congolese counterpart of selling out to the U.S. (the DRC signed on to Project Vault); instead pushing for a Continental approach to mineral development.

How should African policymakers approach the current geopolitical moment? The primary focus should be an aggressive domestication of private ownership and value addition. Predominantly relying on foreign firms and exporting raw commodities will ensure that this time is not different, and will certainly expose countries to abuse by global powers. On the matter of Continental coordination, I am of the view it will only be possible once countries have their own houses in order — the region certainly needs a new model of Pan-Africanism. Coordinating at the Continental level under conditions of domestic weakness results in no more than talking shops, lots of business as usual, and ever-deepening global exploitation. Remember that investment laws and regulations, tax policies, as well as contracts are all still national. That’s where the real action will remain for the foreseeable future.

To be clear, there is a lot not to like about the DRC-U.S. deal. However, the Pan-African critique is fairly weak on the merits. Where was South Africa before the current deal? If Pretoria wants Continental cooperation, it should take the lead and put in the money and time to institutionalize its regional leadership (starting within SADC and then the AU). Talk is cheap.

That said, there is scope for coordination — especially on energy generation (with a focus on regional power pools), transportation and logistics (including railways and ports), and cross-country finance/investment policies. That should be the lens through which to view projects like the Lobito Corridor or the TAZARA refurbishment, as opposed to subordinating them to global geopolitical hyperventilation sessions. The real test for both projects will be in how much de-enclaved commercial activity and tax revenues they generate for the participating countries. It is as simple as that.

Another area of coordination should be around security. A truism that African policymakers should internalize is that you cannot have nice things without the ability to military defend them — especially if you have natural resources. The nature of commodities is that they always attract individuals with a very high risk appetite. Without sufficient deterrence, conflict invariably follows. This is why the Continent should have a more focused approach to security in relation to the resource sector — possibly including putting boots on the ground to enforce peace. There should also be a willingness at the AU to call out global powers (especially the more aggressively-revisionist emerging Middle Powers) that have no qualms fomenting conflicts as an extraction strategy in the region.

Lastly, the discourse on value addition has substantially improved since last time. I recall an impatient younger me being mightily frustrated with consulting work touching on Ghana’s value addition dreams just after the oil started flowing. Back then value addition was transparently fluffy, with everyone still very much tethered to soul-crushing bare-minimum corporate social responsibility (CSR) theater.

We have come a long way since then. First, the (ideological) permission structure for domestic private ownership in the natural resource sector (including in collaboration with governments) is expanding. This has historically been an underrated problem in the region. Ideological commitment to full public ownership has yielded nothing but inefficiency and wholesale pillaging. Unable to run mines well, governments found themselves forced into terribly lopsided contracts with foreign players. Venal politicians gave away national crown jewels for trinkets. Under the circumstances, domestic or regional private players are a good way to inject market logics and efficiencies into the sector, force governments to improve policymaking, de-enclave resource sectors, and ensure that resource windfalls are reinvested in the domestic economy.

I realize that there are lots of people who don’t want to open this can of worms. However, it’s a conversation that must be had. If the region is to realize the gains from mining, African private firms must be heavily involved throughout the value chain.

Second, governments have finally realized that there are immense gains to be made from domestic value addition (they all talk about Indonesia these days); and have therefore moved on to discussing how to address challenges to beneficiation and supply chain development — including infrastructure (especially energy, transport, and logistics) and policy logjams. These are the specific channels through which commodity windfalls are likely to generate growth and jobs in the wider economy.

Here, the recent evolution of Nigeria’s oil sector is instructive (yes, Nigeria). The emerging turnaround is primarily because of more robust involvement by Nigerian private sector players. They have skin in the game and can make long-term bets. They get the political economy. They have nowhere to run, and therefore will stand their ground and move the needle on policy improvements as they advance their interests. They are more likely than foreign firms to de-enclave their operations, including by reinvesting windfalls in non-resource sectors of the economy. And overall, their very presence can be a catalyst for reorienting elite thinking and habits away from two-bit rent-seeking.

I cannot stress this enough. All else equal, domestic private players are a great asset to have if you are a resource-dependent economy.

III: It is important not to lose perspective

Even as the region prepares for a likely commodity boom, I should caution readers against getting carried away by ideas of unlimited riches in Africa.

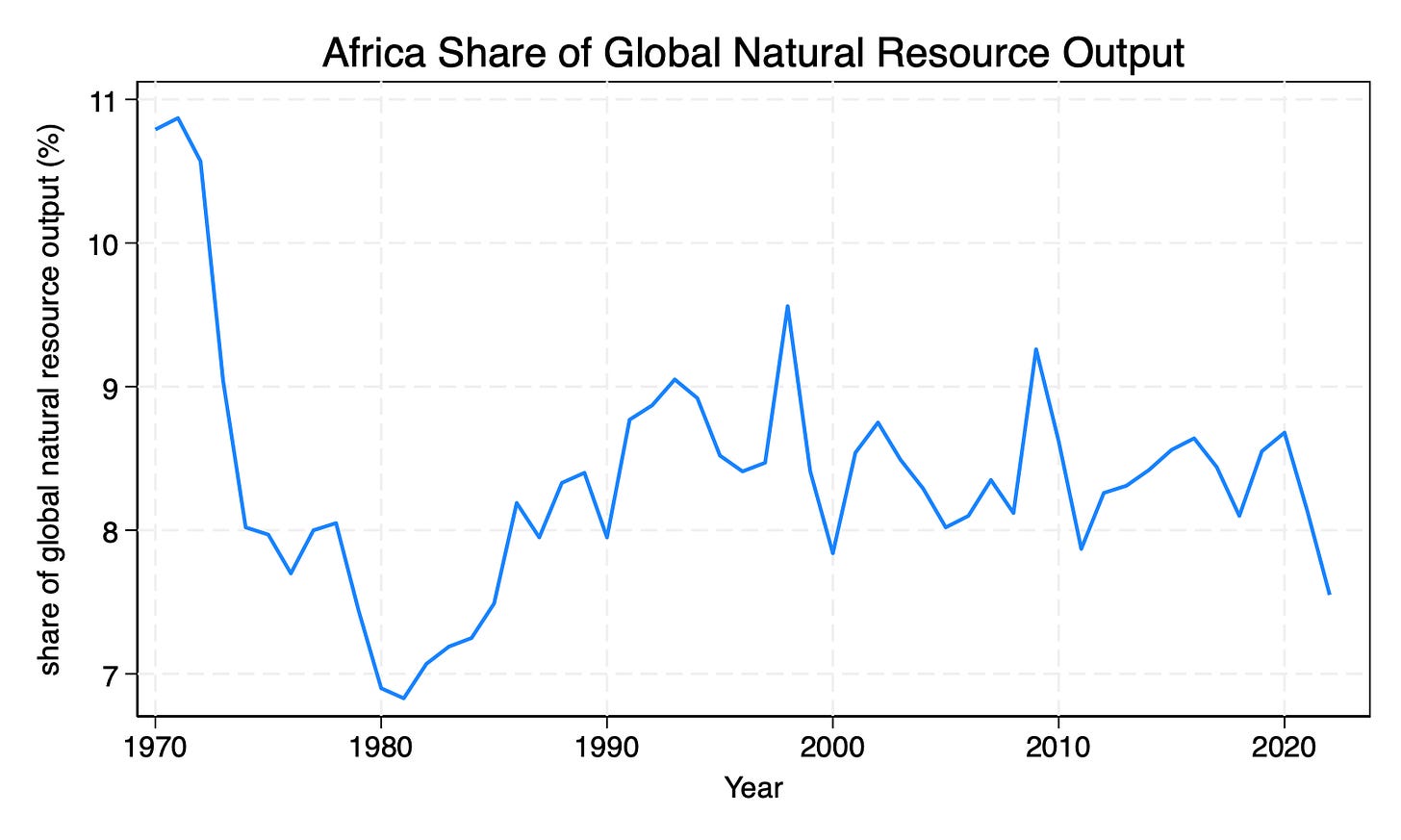

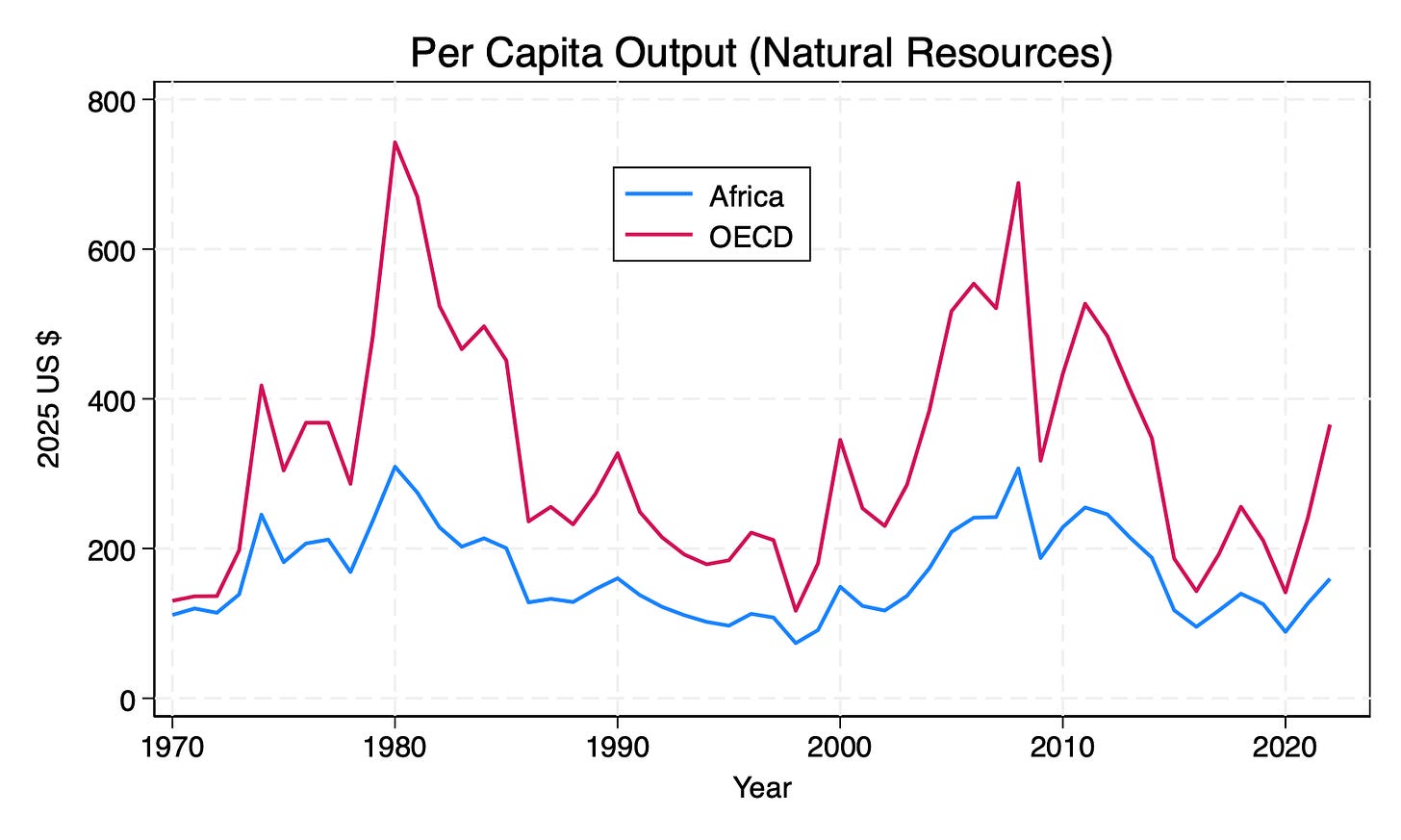

The fact of the matter is that Africa’s share of global natural resource output (averaging below 9% over the last 50 years) far underperforms its share of the global landmass (20%). Furthermore, the historical industrial organization of the sector (foreign ownership, little value addition) means that the region gets little benefit. This is true in both absolute and per capita terms. For instance, the average per capita output of natural resources in the region consistently underperforms the OECD. Some of this reflects the nature of the sector — say Swiss traders re-exporting Congolese minerals. However, the overall point is that when one looks at the historical numbers Africa hasn’t been that rich in natural resources that make it to market.

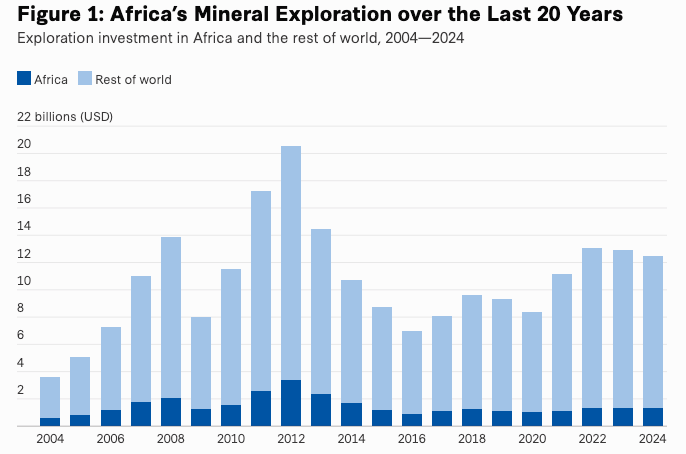

One explanation for this outcome is the historical under-investment in exploration and production. Excluding small-scale “artisanal” mining, the whole of Africa has about as many active mining operations as Australia (25% of Africa’s land mass).

Importantly, the lack of investment in exploration doesn’t make economic sense:

[Africa’s] share of global exploration spending has declined consistently, falling from 16 percent in 2004 to just 10.4 percent in 2024 (Figure 1). This drop is striking given that Sub-Saharan Africa is the most cost-effective region globally for mineral exploration, with the mineral value to exploration spending ratio of 0.8—far outperforming Australia (0.5), Canada (0.6), and Latin America (0.3).

What explains the under-investment in exploration? You often hear standard vibes-based stories about risk, conflict, lack of financing, regulatory uncertainty, and the like. However, all you need to do is pause for a second and look at a historical map of major mining operations on the Continent. In most of those countries, the suggested risk factors have typically followed the onset of resource exploitation. You also tend to see lots of activity in very risky places.

African policymakers should take the lack of investment in exploration as a challenge. Instead of sitting on their hands and waiting to be viewed favorably by international firms, there is an opportunity to grow domestic firms, financing capacities, and value chains on the back of the coming supercycle. A more robust profile of domestic ownership would also create strong incentives for political and business elites to impose operational order on the sector, including via accommodations that will end the exploitative and incredibly violent forms of “artisinal” mining that we have witnessed over the last 35 years.

If policymakers do one thing over the coming commodity supercycle, it should be to ensure a thorough de-enclaving and domestication (including in private hands) of the Continent’s resource sector.