There is an urgent need to unlock labor productivity in African economies

On the need to have the right perspective regarding the ongoing two-decade economic slump in African states

I: A two-decade slump in regional growth rates

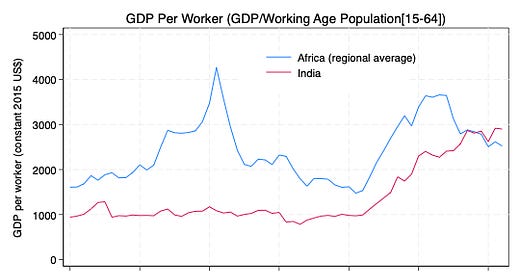

Talk of “Africa’s lost decade” is becoming common again, with evidence from stagnant or declining per capita incomes in African states amidst the ongoing global economic slowdown, the region’s fiscal squeeze, and a two-decade slump in regional growth rates (see figure below). Two dozen African countries are currently in or nearing debt distress as of June 2023 — with Chad, Ghana, and Zambia already in default. While many of these countries face a liquidity rather than a solvency crisis, the current high interest rate environment and their inability to access credit markets mean that they lack the means to buy themselves time to grow out of their high debt/GDP ratios.

In 2022 the region spent 31% of total government revenues to service debts. That is money that could have gone to funding schools, hospitals, roads, water systems, et cetera. Meanwhile, African states are slated to keep paying relatively higher interest rates (some argue unfai…